Reformatory movements and outset of the Hussite Movement

Heresy has been part of Christianity ever since its beginning. In the Middle Ages, it put emphasis on selected parts of the Bible from which it derived its own, usually one-sided conclusions. The Church protected itself against them and persecuted the heretics. The various heretical groups differed in their ideas and operated throughout medieval Europe. The revivalist movement of new devotion (devotio moderna) sought to reform the Church and eradicate disgraceful phenomena in the life of the clergy (pluralism, simony, etc.) and the writing of the English reformist John Wycliffe. John Huss, who strongly opposed the vices in the Church, was burned to death for his ideas in Konstanz on 6 July 1415. Protests against his death and the reformatory movement spread rapidly throughout the country and the society found itself on the verge of the Hussite Revolution.

Jan Hus at the stake, The Jena Codex (ca 1500). Wikimedia Commons. Available here, [26/12/2020].

References

Molnár, A.: Valdenští. Evropský rozměr jejich vzdoru. Praha 2. vydání 1991;

Šmahel, F.: Husitská revoluce I−IV. Praha 2. vyd. 1995−1996;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

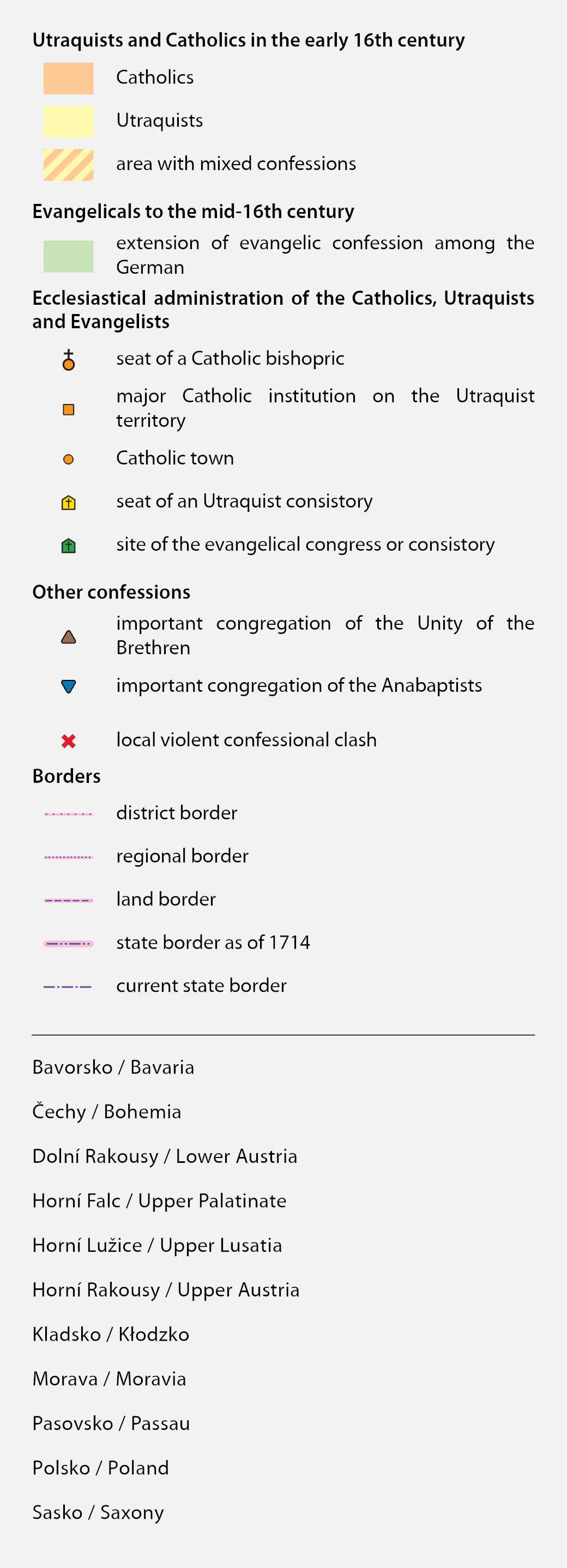

Religious situation in Bohemia and Moravia at the beginning of the 16th century

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, Communion Under both Kinds was professed in the Czech Lands. In the so-called Peace of Kutná Hora of 1485, the Bohemian Land Diet promulgated unity between the Catholic and Utraquists confessions for people of all ranks. The resolution was adopted as a state law, but it did not involve the Unity of the Brethren. Most of the people in Bohemia and Moravia were Utraquist, but the Catholics were a strong minority. In Bohemia, the prevalence of the Utraquists was more pronounced than in Moravia. The Czech-speaking population was largely Utraquist while the Germans were more affiliated to Catholicism.

The image of Christ of Sorrows giving himself in both kinds was created around 1470 for Prague's main Utraquist church, the Church of Our Lady before Týn. Wikimedia Commons. Available here, [26/12/2020]

Kutná Hora (Kuttenberg), a place of religious peace between Catholics and Calixtins in 1485, in: Ottovy Čechy, IV. díl Polabí, Praha 1888, s. 112-113. The Library of Institute of History, CAS.

References

Macek, J.: Jagellonský věk v českých zemích (1471–1526) III. Města. Praha 1998;

Macek, J.: Víra a zbožnost jagellonského věku. Praha 2001;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Confessional situation in Bohemia and Moravia in the pre-White Mountain period

In the relatively tolerant religious milieu (the evangelicals–Utraquists, supporters or the Lutheran or Calvinist reformatory ideas, the Catholics, the Anabaptist /Habáni/ and the Bohemian Brethren, etc.), activities of the Catholic Church started to intensify in the mid-16th century. In 1575, under a pressure from the estates, Emperor Maximilian II promised freedom of religion by issuing the Confessio Bohemica, which was subsequently confirmed by the Letter of Majesty issued by Rudolph II in 1609. However, two years after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, Emperor Ferdinand II had the Letter of Majesty cut to pieces, thus making it invalid.

A commemorative plaque at the former Lesser Town Hall, the place where the Czech Confession was written (1575). Wikimedia Commons. Available here, [26/12/2020].

References

Pánek J. ‒ Tůma O. a kol.: Dějiny českých zemí. Praha 2008, 2018;

Just, J.: 9. 7. 1609. Rudolfův Majestát. Světla a stíny náboženské svobody. Praha 2009;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0