Emigration from Bohemia during the Hussite Movement

The Hussite Movement and its consequences initiated a relatively strong wave of emigration of the Catholic population behind the borders of the land. The emigrants were mostly clerics – priests and monks. They usually headed for places where their orders were active, i.e. a parent, subsidiary or allied convent or to places where the convent owned some property, in particular Moravia, Lusatia, Silesia, the German states or Poland. They took many monastic manuscripts with them, which remained in the foreign monastic libraries.

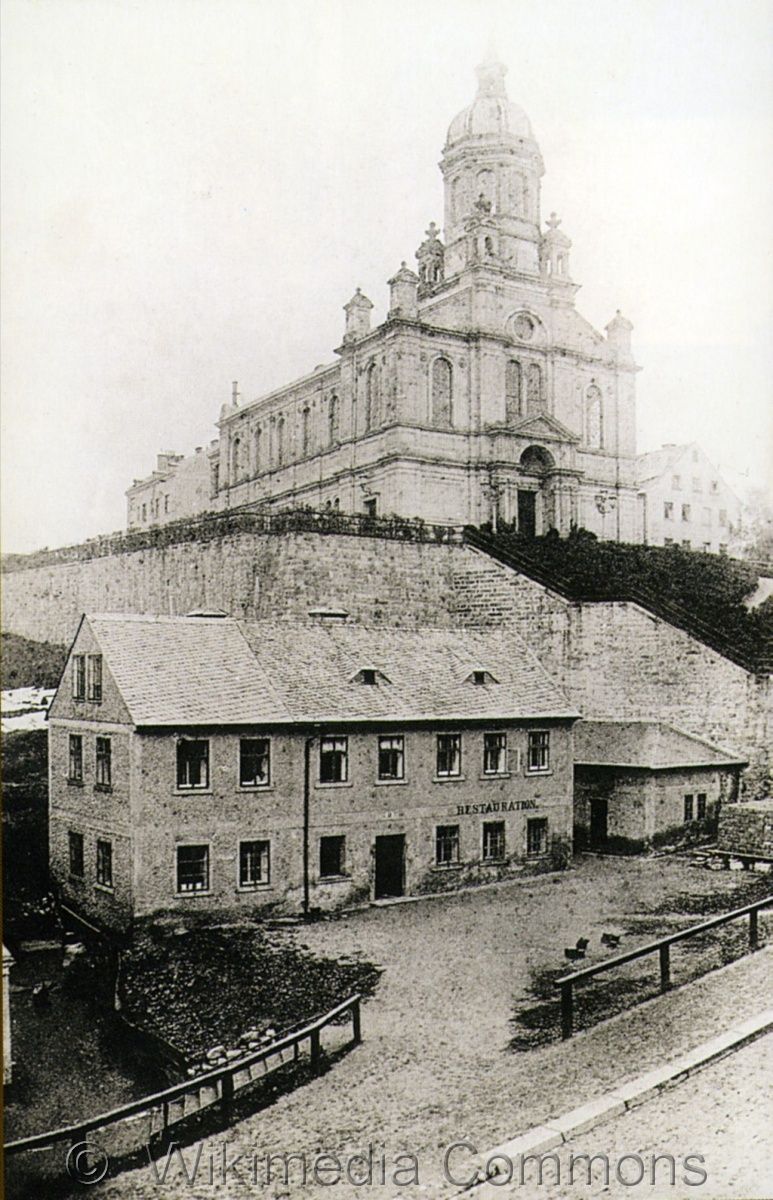

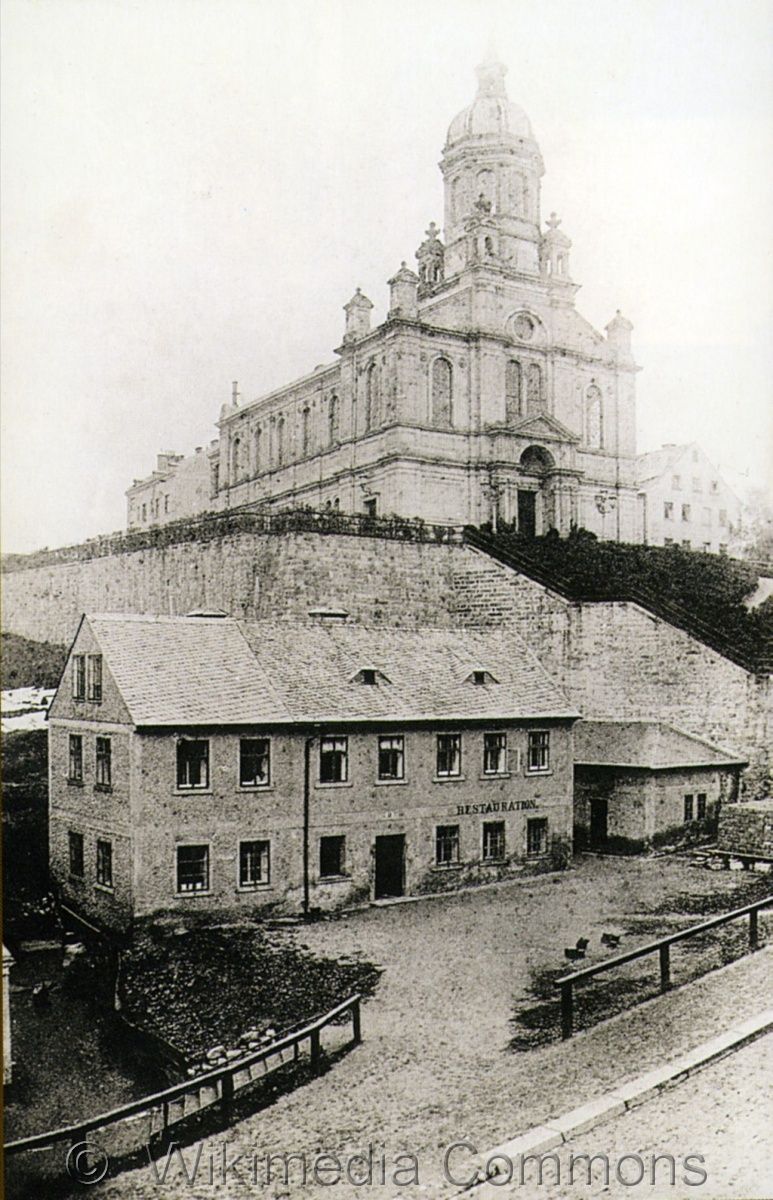

Ojvín (Oybin), monastery of Celestine monks in the Oybin Castle area. Wikimedia Commons. Accessible here [verified 03/04/2020]. Photo © VitVit, 2012

Wrocław, Church of Our Lady on the Sand (Piasek). Wikimedia Commons. Accessible here. [verified 03/04/2020]. Photo © Kroton, 2011

References

Kadlec, J.: Katoličtí exulanti čeští doby husitské. Praha 1990;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Religious emigration from Bohemia between the 16th to 18th centuries

In the 16th century, the Bohemian Brethren who were banished in 1548 emigrated from Bohemia. They usually went to Greater Poland where they established a Polish branch of the Unity of the Brethren and some of the brethren settled down in Prussia. After the Battle of White Mountain and issuance of the Renewed Land Ordinance (1620, 1627), the non-Catholics, i.e. Bohemian Brethren and the Neo- and Old-Utraquists left for Silesia where they established Czech-language Lutheran congregations and the German-speaking exiles established new settlements in the Ore Mountains. Saxony became a destination of new waves of immigrants in the 1670s and 1720s. A renewed Unity of the Brethren was established in Herrnhut (Ochranov).

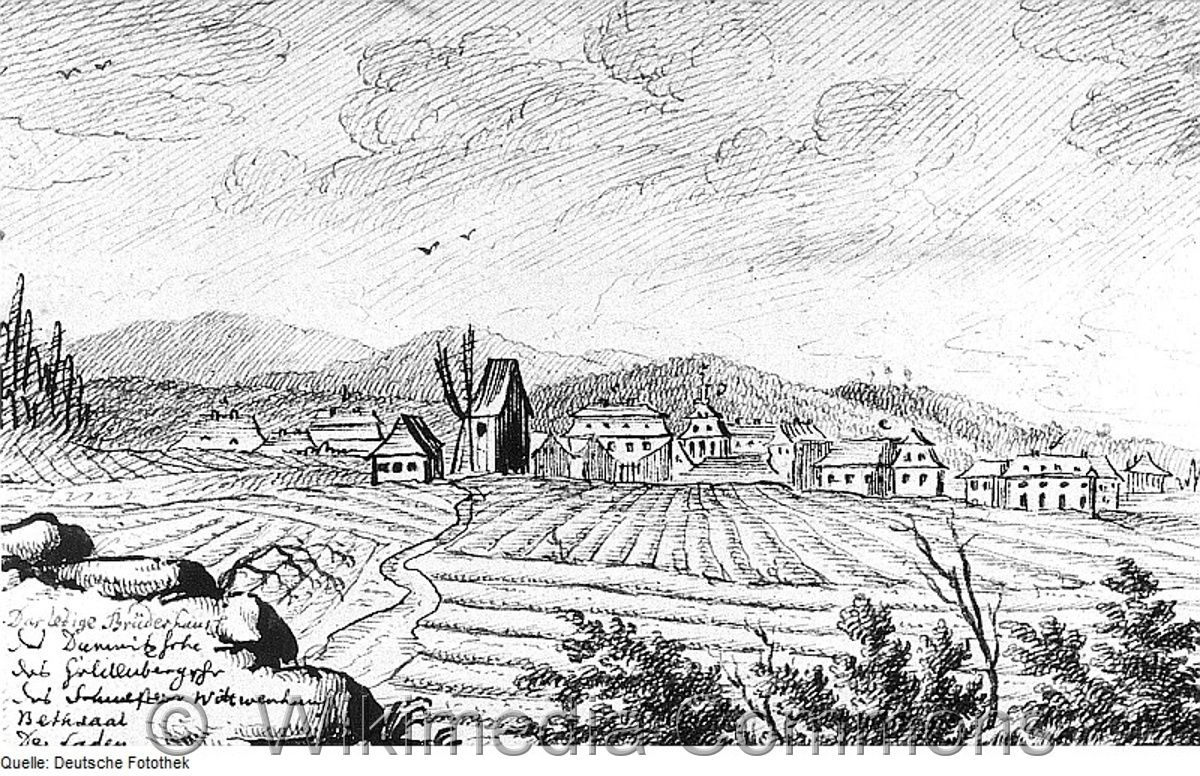

Herrnhut on contemporary illustration (1765). Wikimedia Commons, Deutsche Fotothek. Available here [verified 15/01/2021].

A view of Herrnhut at present time. Wikimedia Commons, Ubahnverleih. Available here [verified 15/01/2021].

References

Bidlo, J.: Jednota bratrská v prvním vyhnanství I–IV. Praha 1900–1932;

Štěříková, E.: Exulantská útočiště v Lužici a Sasku. Praha 2004;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

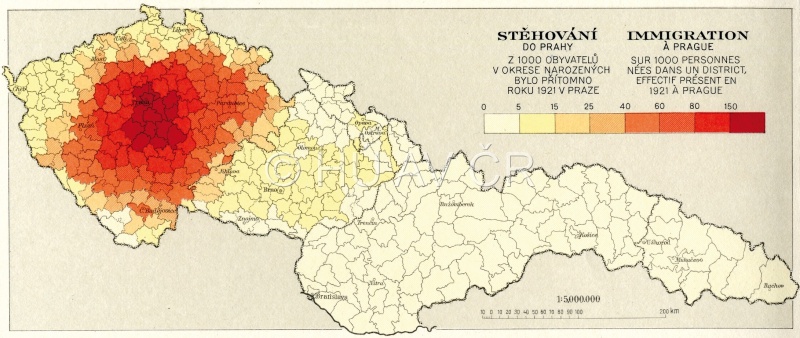

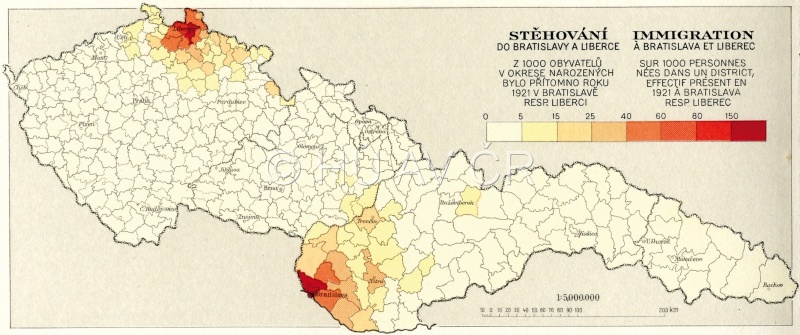

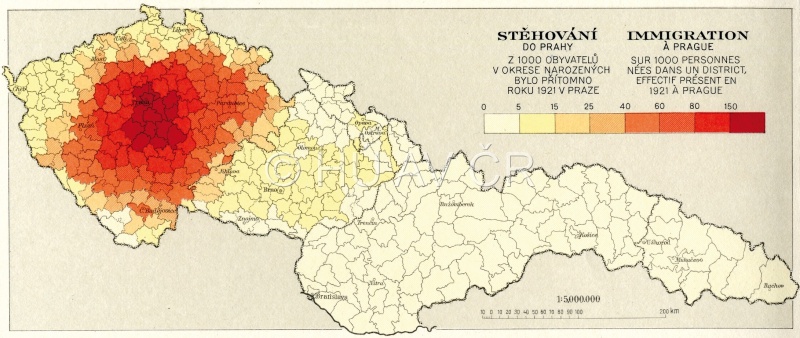

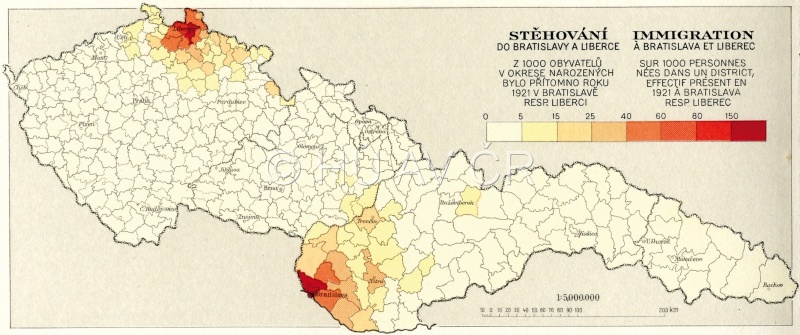

Human migration in the Czech Lands in 1921–1930

The migration balance (i.e. difference between the incoming and outgoing populations) clearly illustrates migration processes on the territory. In the years 1921-1930, they were related to concentration processes connected with the growth of larger towns in the industrially developed northern half of the territory, but also in Hradec Králové and Zlín and larger agglomerations of Prague, Brno and Pilsen. The rural districts depopulated, in particular in south-west Bohemia, the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands, south and east Moravia and the peripheral areas populated by the German ethnic minority (in particular the Broumov Spur, Jeseník Spur and Frýdlant Spur).

Migration of the population to Prague as of 1921, in: Atlas Republiky československé (1935). Map Collection of the Institute of History, CAS. Display map

Migration of the population to Bratislava and Liberec as of 1921, in: Atlas Republiky československé (1935). Map Collection of the Institute of History, CAS. Display map

References

Atlas Republiky Československé. Praha 1935;

Srb, V.: 1000 let obyvatelstva českých zemí. Praha 2004;

Přidalová, I. – Ouředníček, M. – Nemeškal, J.: Historické aspekty migrace v Česku. Specializovaná mapa. Přírodovědecká fakulta Univerzity Karlovy v Praze. In: Ouředníček, M. a kol.;

Atlas obyvatelstva, mapa č. 3.1. Praha 2015. On-line, dostupné z: http://www.atlasobyvatelstva.cz/ [20/03/2020];

Semotanová, E. – Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. – Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Mass relocations of populations in 1938–1943. Violent exchanges and relocations of populations during Nazi expansion in Central Europe

The violent relocations of the populations in Europe intensified after the outbreak of the Second World War. Within the 'Heim ins Reich' policy between 1939 and 1942, about 800,000 ethnic Germans moved from South Tyrol, the Baltic region, Eastern Europe and the Balkans to the German Reich. In the years 1939–1941, over a million Polish citizens were driven from the occupied western part of Poland and the same policy was used by Stalin in the eastern Polish territories. In 1940–1941, the populations were also relocated between Hungary, Yugoslavia and Romania, between Romania and Bulgaria and between France and Germany. The German resettlement policy caused further subsequent war and post-war mass relocations, which also served as a means to deal with issues of ethnic composition in the central and south-east European states.

Convoy of Volhynian Germans' farm wagons heading for new locations in Reichsgau Warthegau in the winter of 1939/1940. Böhmen und Mähren 1940, No. 8, p. 317.

References

Melville, R. – Pešek, J. – Scharf, C. (Hrsg.): Zwangsmigrationen in mittleren und östlichen Europa. Völkerrecht – Konzeptionen – Praxis (1938–1950). Mainz 2007;

Ahonen, P. and others: People on the Move. Forced Population Movement in Europe in the Second World War and its Aftermath. Oxford 2008;

Ther, Ph.: The Dark Side of Nations-States, Ethnic Cleansing in Modern Europe. New York–Oxford 2013;

Pešek, J.: Evropská vyhnání a vysídlení 20. století a velmoci. In: Velmocenské ambice v dějinách. Praha 2015, s. 103–130;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. ‒ Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

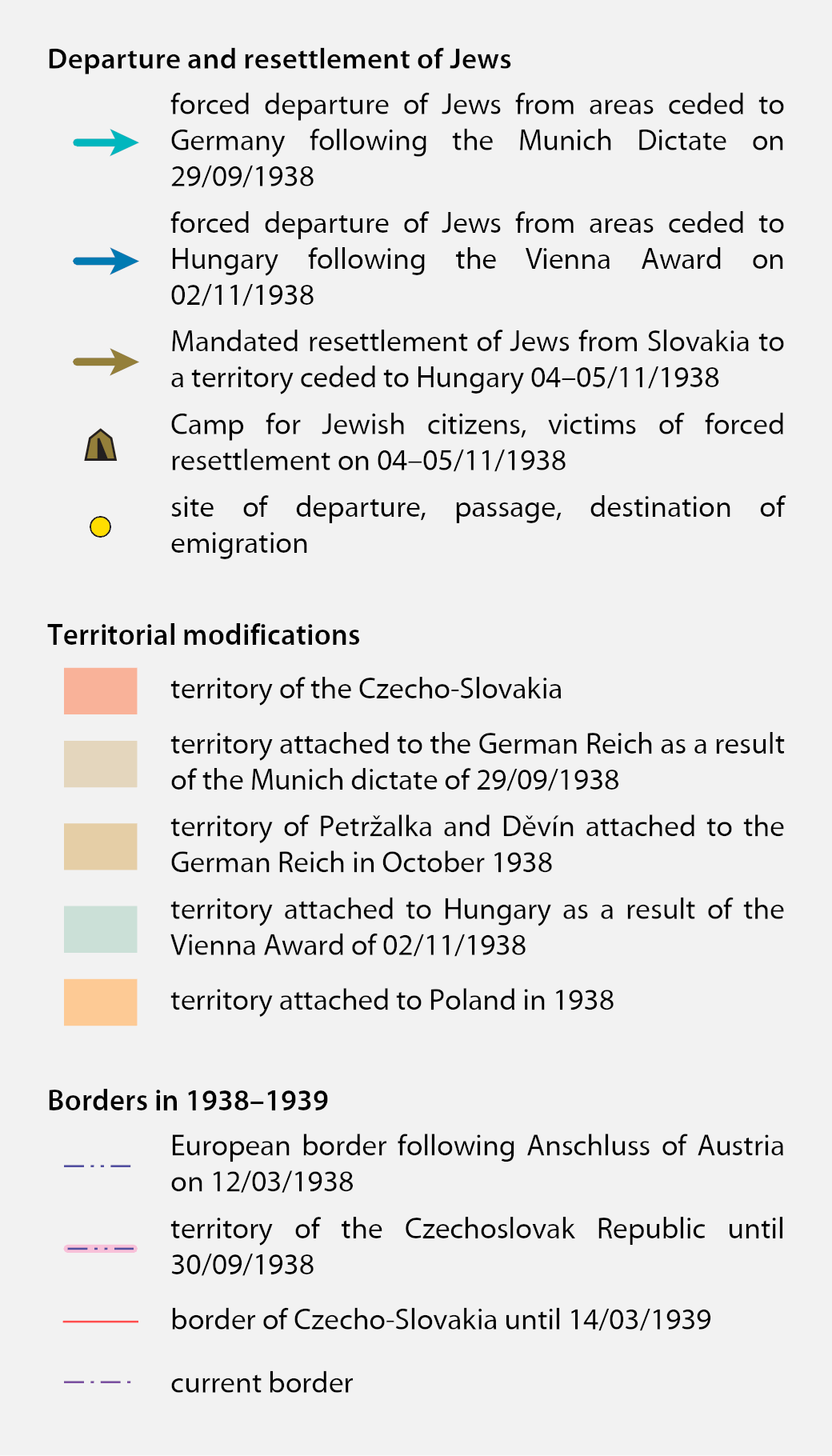

Departure and resettlement of Jews from Czecho-Slovakia (October 1938 – March 1939)

The fate of the Jews – citizens or temporary refugees from the German Reich – was sealed by the dictate of the four powers regarding Czechoslovakia on 29 September 1938. As the map shows, there is no doubt that the Jews hastily left the ceded territories for the interior, but in the spring of 1939, they tried to leave Czecho-Slovakia permanently. Their decisions were fuelled by political changes under the Second Republic and manifestations of anti-Semitism. From 1 October 1938 to 15 March 1939, the number of Jews, the Czechoslovak citizens, dropped by 14,000 people.

The anti-Jewish pogrom from the 9th to 10th November 1938 also affected Czechoslovak Jews in the Sudetenland. The synagogues and prayer rooms did not escape the Nazi frenzy either. They were all architectural gems, which also applied to the Liberec synagogue. Photo R. Karpaš, J. Mohr, P. Vursta, Kouzlo starých pohlednic Liberecka, Liberec 1997. Wikimedia Commons. Accessible here [verified 05/04/2020]

References

Heřman, J.: The Evolution of the Jewish population in Prague 1869–1939. In: Papers in Jewish Demography 1977. Jeruzalém 1980;

Benda, J.: Útěky a vyhánění z pohraničí českého území 1938–1939. Praha 2012;

Semotanová, E. – Zudová-Lešková, Z. – Janata, T. – Seemann, P. et. alli: Frontiers, Massacres and Replacement of Populations in Cartographic Representation Case Studies (15th-20th Centuries). Prague 2015;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. ‒ Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Migrations, Transfers and Exile

The historical development of the Czech Lands has experienced several important migration waves when some of the citizens voluntarily or forcefully left the country for political, religious, social, or economic reasons.

In the older period, emigration was mostly motivated by religion. During the Hussite Era, the Catholics, particularly the clergy, left the Czech Lands while the period from the 16th to the 18th century was characterized by heavy non-Catholic emigration after the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt at Bílá Hora (1620) and the issuance of the Renewed Land Ordinance (1627), which permitted only the Catholic religion in the land. From about the mid-19th century, socio-economic motivation started to prevail – the Czechs emigrated overseas, mainly to the United States of America on a mass scale.

The rise of Nazism and the beginning of the Second World War resulted in large movements of the populations especially in Central and Eastern Europe, which also affected the Czech Lands. The secession of the Sudetenland commanded by the Munich Agreement in September 1938 resulted in a wave of movements of the ethnically Czech population into the interior. The political changes and intensifying anti-Semitism under the Second Republic were followed by the emigration of some of the Jewish population. Immediately after the end of the Second World War, three million Germans were forcibly expelled from Czechoslovakia and the vacated border areas were subsequently resettled. The establishment of communism in Czechoslovakia in 1948 triggered another wave of emigration of those who did not agree with the new regime. The short period of political ease in the 1960s was forcefully broken by the occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968. In the following twenty-year period of the so-called normalisation, more than 200 thousand people left the country voluntarily or forcefully.

This section also concentrates on the main migration processes in Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic, which reflect the main trends in the development of residential structures in the Czech Lands throughout the 20th century and the early 21st century – concentration of population in larger towns and industrial areas, depopulation of the rural areas and the ongoing process of suburbanisation.

Jitka Močičková

Resettlement of the Germans from Podbořany in June 1946. VÚA-VHA Praha.

Authors

historians: Jitka Močičková, Ladislav Hladký, Pavel Krafl, Pavel Kůrka, Jan Němeček, Eva Semotanová, Tomáš Vilímek, Zlatica Zudová-Lešková

geographers: Jan D. Bláha, Tomáš Burda

cartographers: Petra Jílková, Jan D. Bláha, Jiří Cajthaml, Tomáš Janata, Pavel Seemann, Petr Soukup, Růžena Zimová

digital atlas: Tomáš Janata, Petra Jílková, Jiří Krejčí, Jitka Močičková, Eva Semotanová

team of authors

References

Martínek, J. – Martínek, M.: Kdo byl kdo – naši cestovatelé a geografové. Praha 1998;

Vaculík, J.: Češi v cizině 1850–1938. Masarykova univerzita, Brno 2007;

Vaculík, J.: České menšiny v Evropě a ve světě. Libri, Praha 2009;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. ‒ Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

Czech State and Europe in the 20th Century

Historical Milestones, Periods and Consequences