Basic demographic development by the year 1800

The population development in the Czech Lands in the Middle Ages and early modern times resembled the other contemporary European populations. It was characterized by the so-called natural reproduction, i.e. high birth rates, but also high mortality rates. While the mortality rate experienced fluctuations, the birth rate was very stable. On average, women gave birth to four or five children, mostly within marriage (only very few extramarital children were born, but their number grew to 5 % at the end of the 18th century). Most of the adults lived in a marriage for at least some part of their lives. Only Catholic priests and people unable to enter into marriage for various reasons remained unmarried. Due to the importance of a family, other than a cleric or monastic celibate was probably unwanted. Following the Council of Trent, the conditions to enter into marriage became more stringent and the marriage law was subjected to the Church. The Catholic Church did not accept divorce. The rate of mortality depended on external influences and could significantly increase (e.g. due to crop failures, spreads of epidemics or wars). On average, the life expectancy was 25-27 years, but if the children survived the infantile age, they had a chance to live 52-55 years. About a fifth of the newborns died during the first year of life, another quarter died in the following ten years. Due to physiologic differences between the sexes, excessive mortality rate affected boys in the first years of life while girls and young women died more often at the age of 15-34. Fewer women lived to the old age than men. In favourable conditions, the population could grow relatively quickly, but conversely, it could sharply drop in unfavourable conditions. There were large regional differences even over relatively short distances because epidemics or wars could hit only certain locations and spare others.

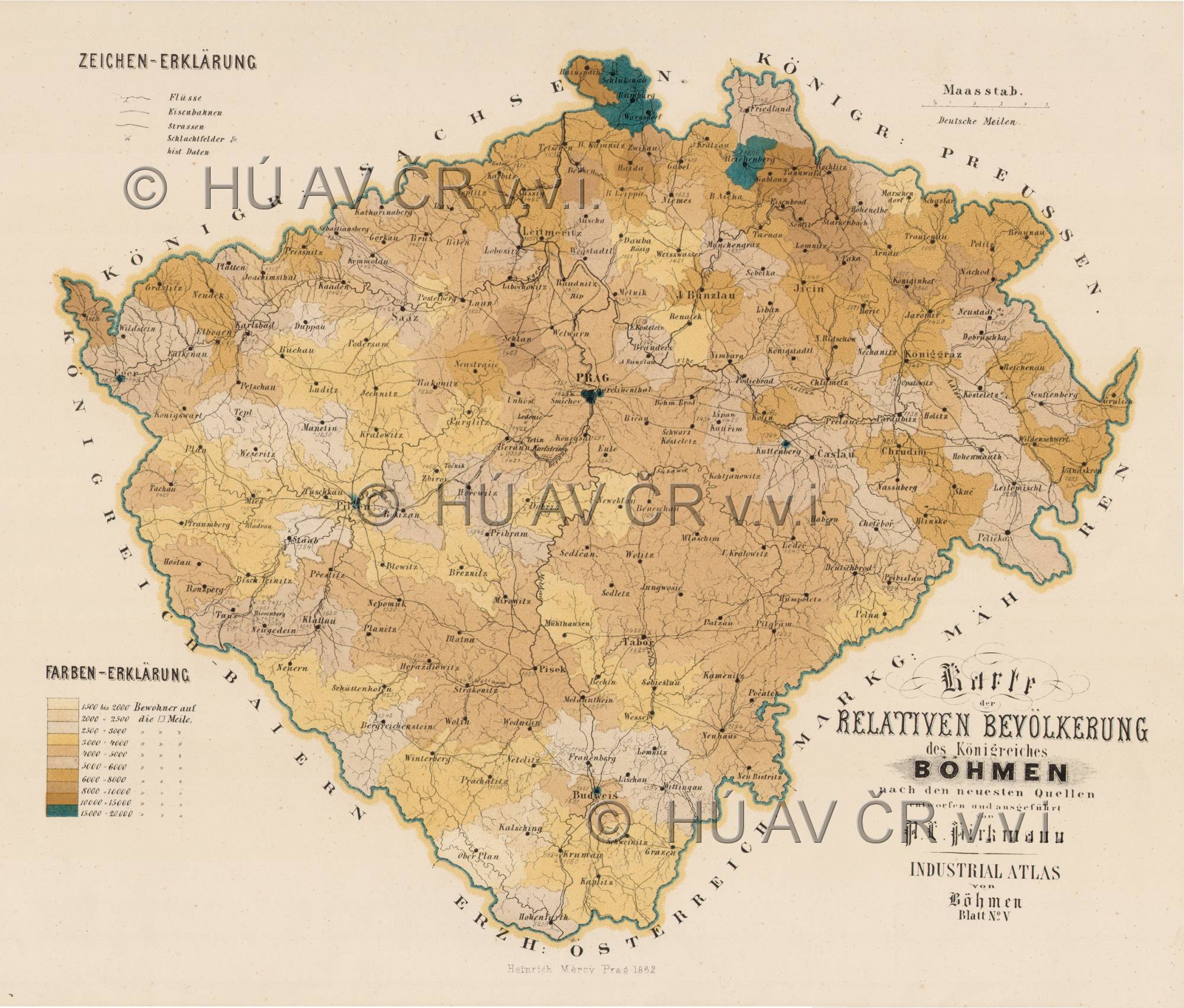

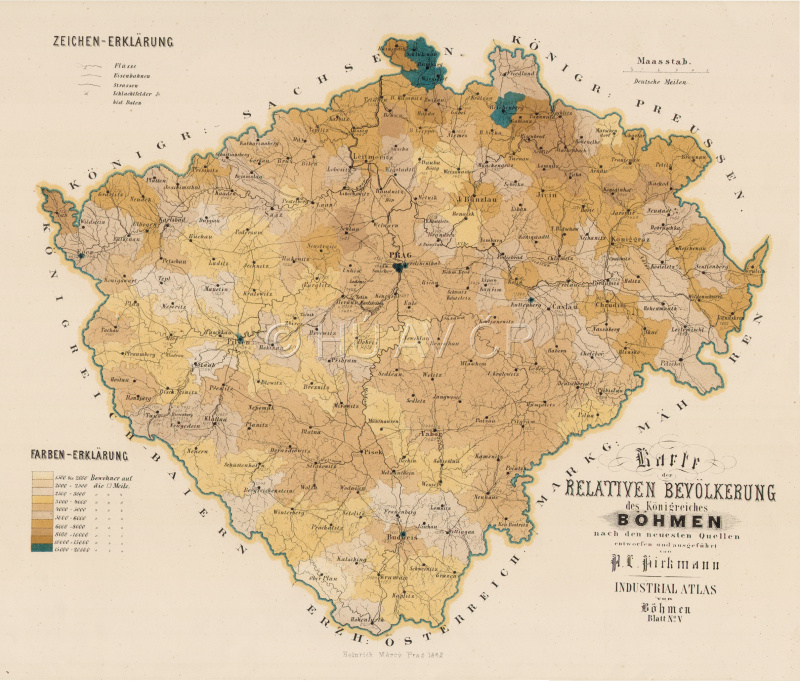

At that time, the population development was strongly affected by societal development (political crises, wars) and economic progress, in particular, technical advance in agriculture that expanded the cultivated land and production. Climatic changes were the third factor: by the 13th century, the climate warmed slightly in Europe. This fact enabled the settlements to be moved from the old territory (uninterruptedly populated since the Neolithic) to higher altitudes. At the end of the 12th century, a continuous population reached the altitude of 500-600 meters above sea level and thus more than half of the territory became populated. Due to the orographic circumstances, this colonization, first from internal sources, was more significant in Bohemia than in Moravia where fertile lowlands covered a larger area. The population of the Czech Lands exceeded one million for the first time. The following 13th and 14th centuries were a period of rapid population growth, which was also caused by German colonists who headed for towns and higher altitudes of the border ranges and the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands. It is estimated that about three million people lived on today's territory of the Czech Lands at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries. However, in the 14th century, population growth ended and changed into decline. Like in many other European countries, this was caused by climatic changes (gradual cooling), exhaustion of the feudal economy, change of the epidemiological situation (in 1347, black plague, Pasteurella pestis, spread in Europe again) and political and religious destabilization that led to numerous wars. The key factors in the population development of the Czech Lands were plague epidemics in 1380 and the Hussite Wars (1419-1434) that most affected central and south Bohemia. The living conditions improved and the population increased at the end of the 15th century when the international situation calmed down. In the early 16th century, the population reached around 1.7 million and continued to grow in favourable conditions. However, frequent epidemics reduced the population at the end of the 16th century and this situation worsened in the first half of the 17th century when a long war accompanied the epidemic and contributed to the overall collapse of the economy. During the Thirty Years' War, the Czech Lands were affected by three epidemics of black plague (1624–1626, 1631, 1648–1649), dysentery and typhoid that were also spread by the military. The most affected areas were fertile regions of central Bohemia and central and south Moravia where the losses of the population were the heaviest, reaching up to 40-50 %. The estimated total losses in the population were 30 %.

The losses were relatively quickly replenished after the end of the war. The marriages and birth rates improved and the mortality rate was favourable. It increased only during the last two plague epidemics on our territory (1680 and 1713-1715), during the wars in the mid-18th century (1740-1741, 1757–1763) and a great crop failure in 1771-1772. At that time, about 250,000 people (about a tenth of the population) died of malnutrition in Bohemia; in Moravia, the losses were more moderate. At the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, about 2.5 million people lived in the Czech Lands and one million more in only fifty years. The drop of the population in 1772 was replenished within 15 years so that the population increased to 4.8 million in 1800.

| year | population in thousands | people per sq. km |

|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 630 | |

| 1050 | 680 | 8,7 |

| 1200 | 1 235 | 15,8 |

| 1400 | 2 800–3 270 | 35,9–41,9 |

| 1529 | 1 675 | 21,2 |

| 1600 | 2 100 | 26,6 |

| 1650 | 1 650 | 20,9 |

| 1700 | 2 573 | 32,6 |

| 1750 | 3 500 | 44,4 |

References

Boháč, Z.: Postup osídlení a demografický vývoj českých zemí do 15. století. Historická demografie 12, 1987, s. 59–87;

Dějiny obyvatelstva českých zemí. Praha 1995.

Basic demographic development by the year 1800

The population development in the Czech Lands in the Middle Ages and early modern times resembled the other contemporary European populations. It was characterized by the so-called natural reproduction, i.e. high birth rates, but also high mortality rates. While the mortality rate experienced fluctuations, the birth rate was very stable. On average, women gave birth to four or five children, mostly within marriage (only very few extramarital children were born, but their number grew to 5 % at the end of the 18th century). Most of the adults lived in a marriage for at least some part of their lives. Only Catholic priests and people unable to enter into marriage for various reasons remained unmarried. Due to the importance of a family, other than a cleric or monastic celibate was probably unwanted. Following the Council of Trent, the conditions to enter into marriage became more stringent and the marriage law was subjected to the Church. The Catholic Church did not accept divorce. The rate of mortality depended on external influences and could significantly increase (e.g. due to crop failures, spreads of epidemics or wars). On average, the life expectancy was 25-27 years, but if the children survived the infantile age, they had a chance to live 52-55 years. About a fifth of the newborns died during the first year of life, another quarter died in the following ten years. Due to physiologic differences between the sexes, excessive mortality rate affected boys in the first years of life while girls and young women died more often at the age of 15-34. Fewer women lived to the old age than men. In favourable conditions, the population could grow relatively quickly, but conversely, it could sharply drop in unfavourable conditions. There were large regional differences even over relatively short distances because epidemics or wars could hit only certain locations and spare others.

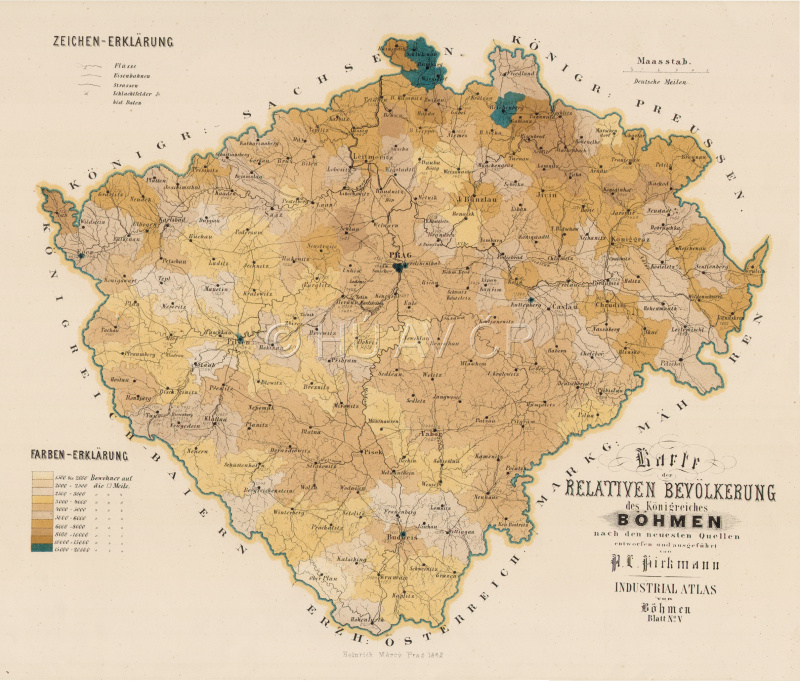

At that time, the population development was strongly affected by societal development (political crises, wars) and economic progress, in particular, technical advance in agriculture that expanded the cultivated land and production. Climatic changes were the third factor: by the 13th century, the climate warmed slightly in Europe. This fact enabled the settlements to be moved from the old territory (uninterruptedly populated since the Neolithic) to higher altitudes. At the end of the 12th century, a continuous population reached the altitude of 500-600 meters above sea level and thus more than half of the territory became populated. Due to the orographic circumstances, this colonization, first from internal sources, was more significant in Bohemia than in Moravia where fertile lowlands covered a larger area. The population of the Czech Lands exceeded one million for the first time. The following 13th and 14th centuries were a period of rapid population growth, which was also caused by German colonists who headed for towns and higher altitudes of the border ranges and the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands. It is estimated that about three million people lived on today's territory of the Czech Lands at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries. However, in the 14th century, population growth ended and changed into decline. Like in many other European countries, this was caused by climatic changes (gradual cooling), exhaustion of the feudal economy, change of the epidemiological situation (in 1347, black plague, Pasteurella pestis, spread in Europe again) and political and religious destabilization that led to numerous wars. The key factors in the population development of the Czech Lands were plague epidemics in 1380 and the Hussite Wars (1419-1434) that most affected central and south Bohemia. The living conditions improved and the population increased at the end of the 15th century when the international situation calmed down. In the early 16th century, the population reached around 1.7 million and continued to grow in favourable conditions. However, frequent epidemics reduced the population at the end of the 16th century and this situation worsened in the first half of the 17th century when a long war accompanied the epidemic and contributed to the overall collapse of the economy. During the Thirty Years' War, the Czech Lands were affected by three epidemics of black plague (1624–1626, 1631, 1648–1649), dysentery and typhoid that were also spread by the military. The most affected areas were fertile regions of central Bohemia and central and south Moravia where the losses of the population were the heaviest, reaching up to 40-50 %. The estimated total losses in the population were 30 %.

The losses were relatively quickly replenished after the end of the war. The marriages and birth rates improved and the mortality rate was favourable. It increased only during the last two plague epidemics on our territory (1680 and 1713-1715), during the wars in the mid-18th century (1740-1741, 1757–1763) and a great crop failure in 1771-1772. At that time, about 250,000 people (about a tenth of the population) died of malnutrition in Bohemia; in Moravia, the losses were more moderate. At the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, about 2.5 million people lived in the Czech Lands and one million more in only fifty years. The drop of the population in 1772 was replenished within 15 years so that the population increased to 4.8 million in 1800.

| year | population in thousands | people per sq. km |

|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 630 | |

| 1050 | 680 | 8,7 |

| 1200 | 1 235 | 15,8 |

| 1400 | 2 800–3 270 | 35,9–41,9 |

| 1529 | 1 675 | 21,2 |

| 1600 | 2 100 | 26,6 |

| 1650 | 1 650 | 20,9 |

| 1700 | 2 573 | 32,6 |

| 1750 | 3 500 | 44,4 |

References

Boháč, Z.: Postup osídlení a demografický vývoj českých zemí do 15. století. Historická demografie 12, 1987, s. 59–87;

Dějiny obyvatelstva českých zemí. Praha 1995.