Bohemians in Austria-Hungary and other states of Europe

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the most frequent reason to leave the Czech Lands was a bad socio-economical situation. The Austrian authorities initially tried to direct the immigration to the Military Frontier (Croatia, Slavonia, Banat). In the second half of the 19th century, many Czechs left for Czarist Russia (Volhynia, Crimea, North Caucasus) and the Balkans (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Bulgaria). At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, people also left for Galicia, Bukovina, Hungary, Austrian Littoral, and Dalmatia within internal emigration. Throughout the 19th century, the number of Czechs in Vienna grew and the Czech labourers and craftsmen traditionally moved to neighbouring Germany.

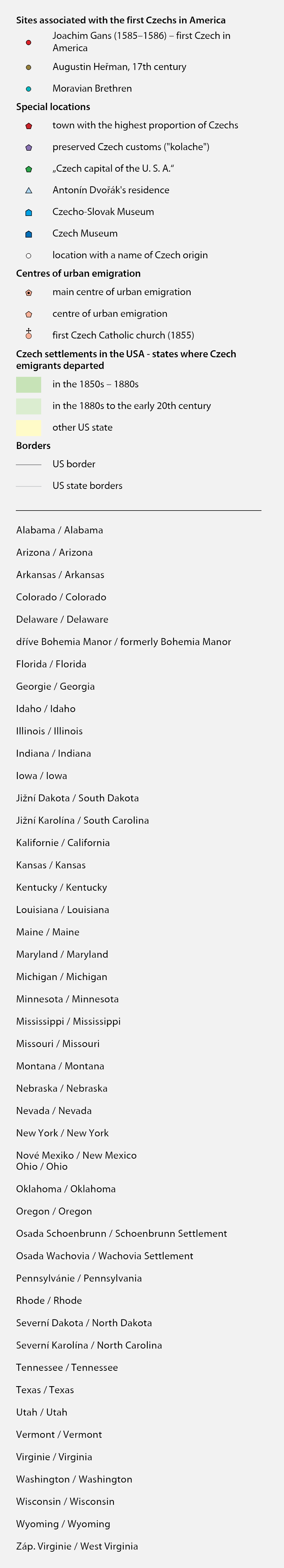

Illustration of new colonists in Banat, Bela Crkva in Meyers Universum (1833–1861). Private collection

References

Vaculík, J.: Češi v cizině 1850–1938. Brno 2007;

Vaculík, J.: České menšiny v Evropě a ve světě. Praha 2009;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Bohemian explorers from the 17th to the early 20th century

The Czechs contributed to the discovery of the world ever since the 17th century mainly as missioners in the colonies, but travels and expeditions of private or official character developed in the 19th century. There were numerous Czech explorers, notably T. Haenke, E. Holub, J. Payer, J. Kořenský or the enigmatic 'globetrotter' E. S. Vráz. Scientific expeditions brought new findings in the area of botany (F. W. Sieber, A. V. Frič), history (E. Glaser, A. Musil), or geography (J. V. Daneš, K. Absolon). One of the most important persons was the promoter, collector, and supporter of explorers Vojtěch Náprstek.

Alois Musil as chief of the Beni Sachs tribe (1901). Wikimedia Commons. Accessible here [verified 07/04/2020]

Jiří Viktor Daneš, J. Shirley and Karel Domin during a tour of Tambourine Mountains in Eastern Australia, in: DANEŠ, J. V. - DOMIN, K. Dvojím rájem. Prague: J. Otto, 1925. Accessible here[verified 07/04/2020]

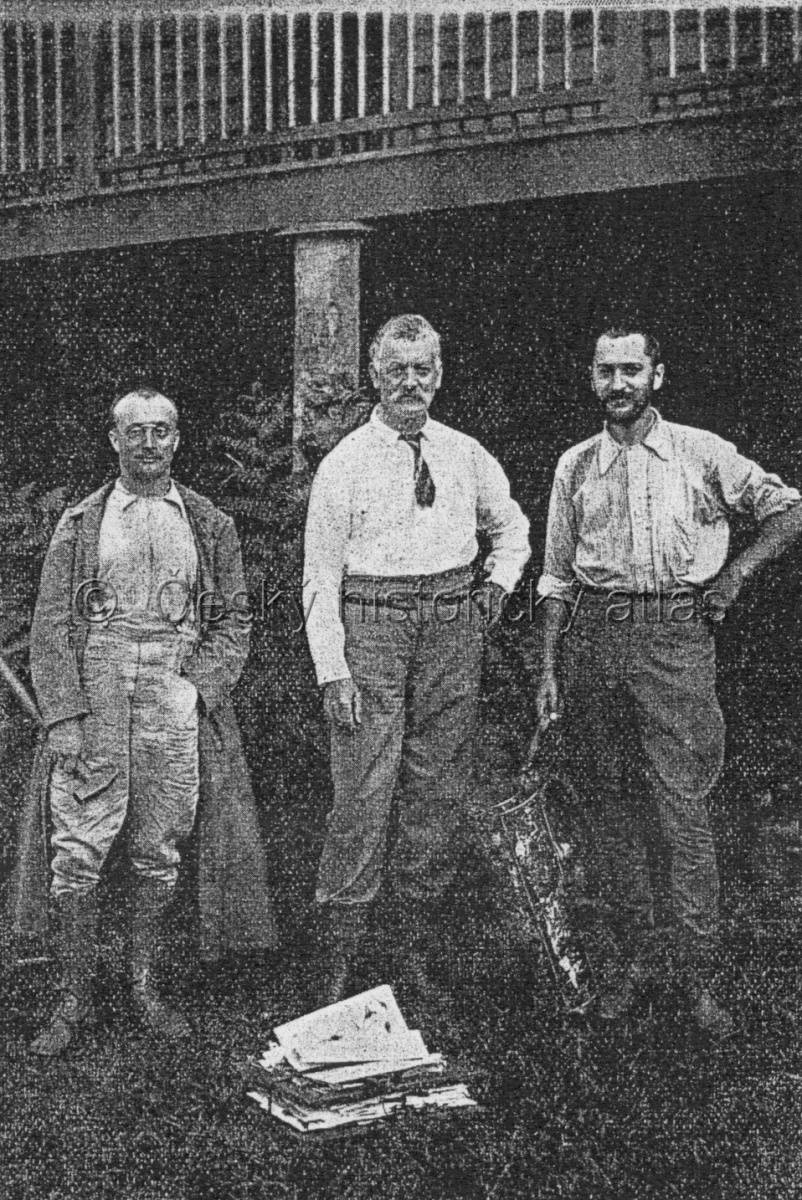

Jacket of Emil Holub's travelogue with illustration of Holub's expedition, in: Holub, E., Von der Kapstadt ins Land der Maschukulumbe, Wien 1890. Private collection

References

Martínek, J. – Martínek, M.: Kdo byl kdo – naši cestovatelé a geografové. Praha 1998;

Rozhoň, V.: Čeští cestovatelé a obraz zámoří v české společnosti. Praha 2005;

Borovička, M.: Velké dějiny zemí Koruny české. Tematická řada. Cestovatelství. Praha – Litomyšl 2010.

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Czech traces in the world

At present, there are several million people of Czech origin living in the world. Czech enclaves had emerged ever since the Thirty Years' War, but emigration on a larger scale took place especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the Czech traces in the world also have the form of memorials or geographical names connected with Czech discoverers, scientists, explorers, or locations of military fame. Czech politicians, entrepreneurs (e.g. the Baťa Company), and above all artists left behind significant traces in the form of buildings and other works of art, literature, music or film.

Ruin of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall designed by the Czech architect Jan Letzel from 1915. Photo Eva Semotanová, 2009

Sculpture of St. John Nepomucene (Nyasvizh, Belarus). Photo Jiří Martínek, 2013

Commemorative plaque for the insurgents of 1918 (Kotor, Montenegro). Photo Jiří Martínek, 2002

Ivan Olbracht Monument (Kolochava, Ukraine). Photo Jiří Martínek

Czechoslovak RAF Airmen Memorial (Broowood, United Kingdom). Photo Jiří Martínek

References

Ševčík, O. – Beneš, O.: Architektura 60. let: zlatá šedesátá v české architektuře 20. století. Praha 2009;

Martínek, J. – Martínek, M.: Kdo byl kdo – naši cestovatelé a geografové. Praha 1998;

Ševeček, O. – Jemelka, M.: Tovární města Baťova koncernu. Evropská kapitola globální expanze. Praha 2016;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. ‒ Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Czech immigrants in the United States of America (1910)

The main reasons for the mass emigration of the Czechs in the 19th and early 20th centuries were socio-economic rather than political. Mass emigration overseas, mainly the United States of America, started in the mid-19th century. The emigration waves were the strongest in the 1860s and 1880s and before the First World War. Many emigrants desired their own land and settled down as farmers in the Midwest and Texas.

Bohemian National Cemetery (Chicago, USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

National Czech and Slovak Museum (Cedar Rapids, USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

Thalia Hall and St. Procopius' Church (Pilsen, Chicago, USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

St. Vitus' Church (Pilsen district, Chicago, USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

References

Polišenský, J.: Úvod do studia vystěhovalectví do Ameriky I–II. Praha 1992–1996;

Dubovický, I.: Češi v Americe – Czechs in America. Praha 2003;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Cajthaml, J. a kol.: Akademický atlas českých dějin. Praha 2014, 2. akt. Vydání 2016.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

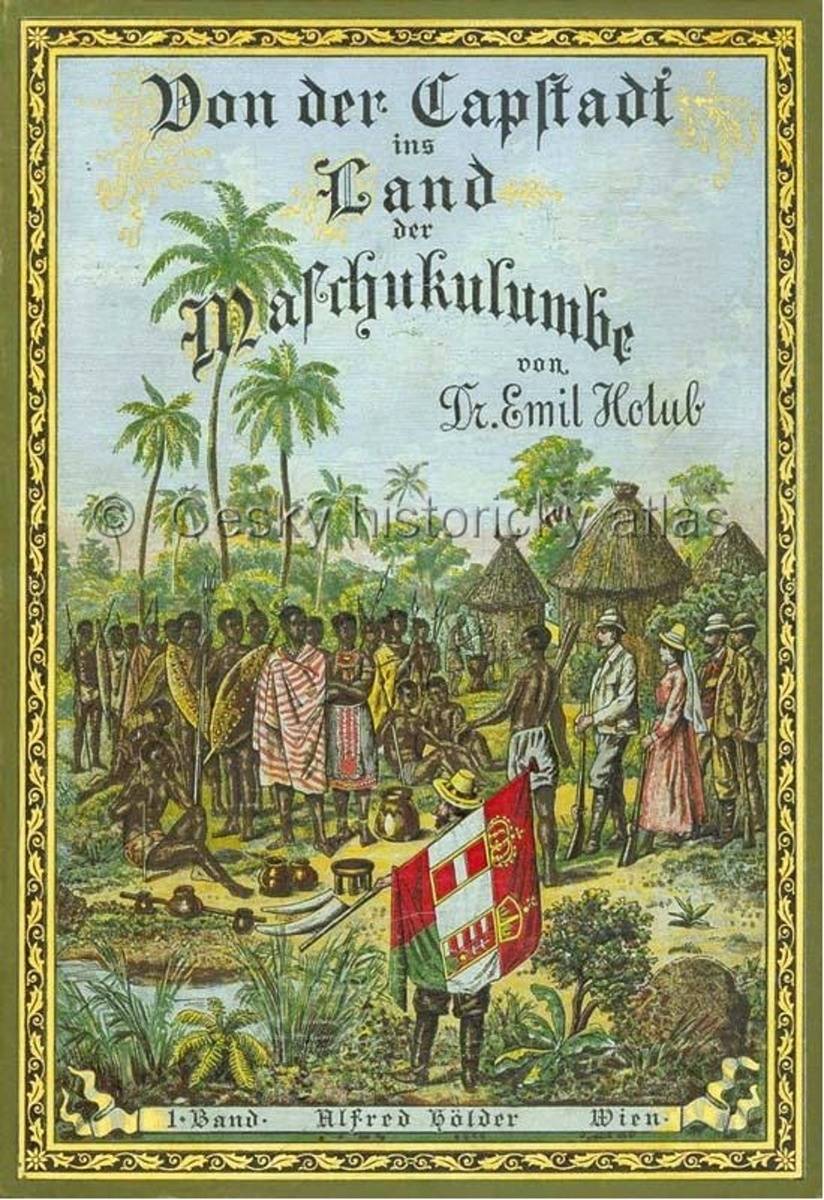

Czechs in the United States of America

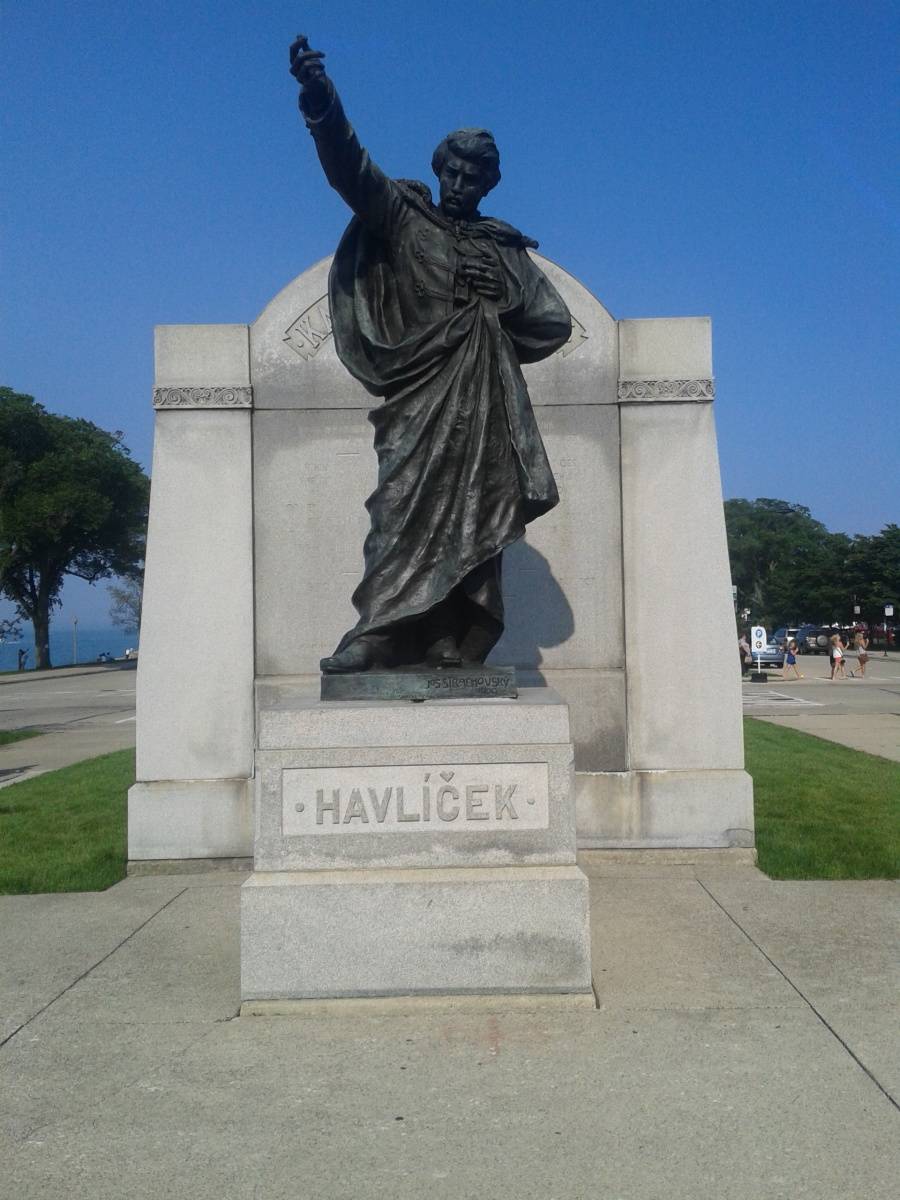

The United States of America was a traditional destination of Czech emigration. The first compatriots departed as early as the late 16th century, but more massive expansions took place in the 19th and early 20th centuries for socio-economic reasons and later, in the 20th century for political and economic reasons. The regions for which the Czech immigrants headed gradually changed according to their professions (labourers, farmers, or craftsmen). Although the Czech communities of compatriots did not evade assimilation, descendants of Czech immigrants still keep traditional Czech customs to some extent and contact with the land of their ancestors.

Statue of Karel Havlíček Borovský in today's centre of Chicago (USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

Bohemian National Cemetery, a memorial to the victims on the SS Eastland passenger ship from 24 July 1915 (Chicago, USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

Grave of J. O. Kostner, a leading representative of the Czech minority (Chicago, USA). Photo Jaroslav Kříž, 2015

References

Mucha, L.: Česká místní jména v USA, Sborník Československé společnosti zeměpisné 70, 1965, s. 136–144;

Polišenský, J.: Úvod do studia vystěhovalectví do Ameriky I–II. Karolinum, Praha 1992, 1996;

Akademická encyklopedie českých dějin. Praha, 2007, hesla Česko-americké vztahy (sv. 2, s. 101–110), Češi ve Spojených státech amerických (sv. 3, s. 357–364);

Kříž, J. – Křížová, L.: Střípky z českého Chicaga: edice dokumentů k dějinám Čechů v americkém Chicagu v letech 1848-1918. Praha 2017;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. ‒ Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

Czech settlement of Banat

Czech colonisers had arrived in the Military Frontier area at Banat since the 1820s and established new villages there. Although the complicated life conditions led to the gradual extinction of some villages, secondary migration to more fertile areas or overseas or re-emigration to Czechoslovakia after the Second World War and after 1989, six Czech villages and several other populated areas with a strong Czech minority have survived in Rumanian and partly Serbian Banat, still keeping the Czech character and culture.

View of Eibenthal in a closed valley from a cemetery above the village. Photo Markéta Šantrůčková, 2016

Place where the village of Elizabeta was probably located. Photo Markéta Šantrůčková, 2012

Gârnic (Gerník) is the largest Czech village. Photo Markéta Šantrůčková, 2010

Rovensko with fields that border on the individual houses. Photo Markéta Šantrůčková, 2010

Šumice in the autumn. Photo Václav Fanta, 2017

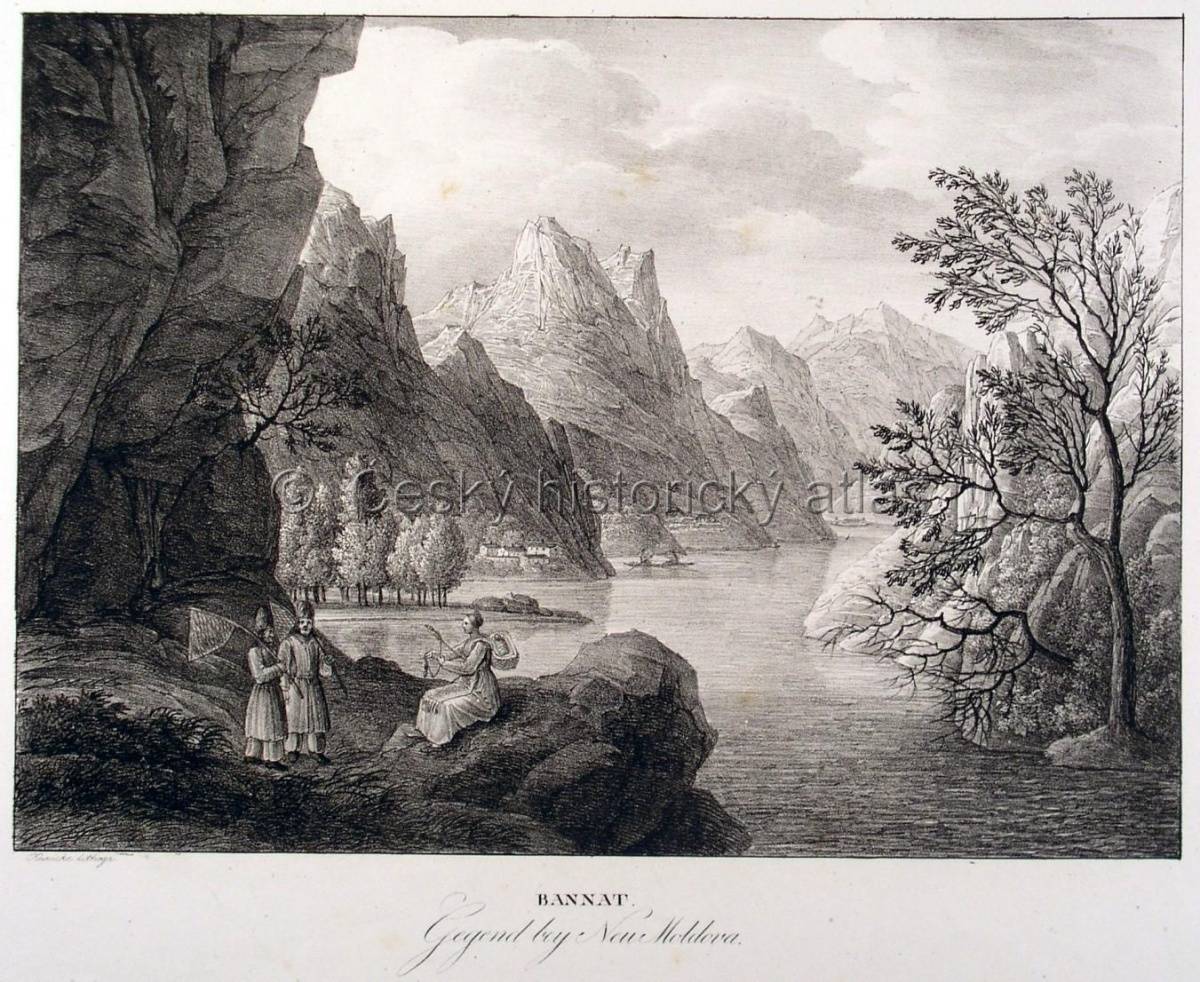

Surroundings of Moldova Nouă (Nová Moldava) in a period illustration. The first Czech colonists arrived there at about that time, in: Kunike, A., Zwey hundert und sechzig Donau-Ansichten. Wien 1826. Private collection

References

Secká, M.: Češi v rumunském Banátu. In: Češi v cizině 8. Praha 1995, s. 92–115;

Gecse, D.: Historie českých komunit v Rumunsku. Praha 2013;

Kovář, P. (ed.): Přenesená krajina: český venkov v rumunském Banátu. Praha 2019;

Semotanová, E. ‒ Zudová-Lešková, Z. ‒ Močičková, J. ‒ Cajthaml, J. ‒ Seemann, P. ‒ Bláha, J. D. a kol.: Český historický atlas. Kapitoly z dějin 20. století. Praha 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0